Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Encampments (2025) Film Review

The Encampments

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Definitions of antisemitism which explicitly make right wing Christian sentiment acceptable but accuse Jewish peace activists of hating themselves; police officers doing nothing whilst young men wearing Israeli flags punch and kick passive students; news broadcasts leading on sport whilst charities plead for attention to be turned to thousands of starving children. We are rapidly reaching the point where even the most casual observers can tell that there’s something odd about the way the conflict in Gaza is being handled. But why?

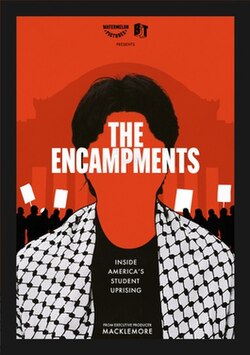

Treating popular conspiracy theories with appropriate disregard, Kei Pritsker and Michael T Workman’s documentary explores the protests that took place on university campuses and, in so doing, makes discoveries which may have far wide-reaching relevance, as well as uncovering a spirit of resistance and solidarity which will warm the spirits of those who have found themselves despairing at the world’s inaction.

The opening salvos come from those opposed to the encampments’ existence, and the language used is as striking as it is disturbing. “These little Gazas are disgusting cesspools of antisemitic hate, full of pro-Hamas sympathisers, fanatics and freaks,” says one politician, knowingly soliciting dangerous emotions with terms much like those used against Jewish people in the past. Like all the speakers, he’s significantly older and more powerful than those he condemns, yet he has no hesitation about kicking downwards. Others call them terrorists, claim they’re brainwashed, and try to dismiss them with patronising speculation about what they might have seen on TikTok.

There is a notable lack of engagement with the issues that the protests are addressing. Of course, when this film takes its turn as a target, some will claim that this a product of selective quoting, and it’s true that documentary makers have that power, but in this case the evidence doesn’t bear it out – besides which, even half a dozen people making such remarks without immediately losing their positions would, in normal times, be shocking in itself.

Balancing those remarks within the film itself are after-the-fact interviews with a number of the protest leaders, plus a good deal of footage of the encampments themselves. This is limited to the US and focuses primarily on Columbia, where the movement began. One interviewee recalls that she chose to study there because it was reputed to have the country’s best human rights programme. Its role in protests against the Vietnam War is duly noted, as is the fact that some of the staff members objecting to the encampments actually participated in those, and have spoken of their pride at having done so.

Given the surrounding narrative, it may well be true that the encampments make some Jewish students feel unsafe, but at Columbia, at least, that fear would seem to be misplaced. “I think we’re here because we are Jews,” says one woman leading a number of others in song. It’s her faith, she explains, that leads her to believe that everyone was made in the image of God, and to celebrate and defend that divine spark regardless of the faith of others.

The story of the protests takes in efforts to force a shutdown by try to cut off supplies of food and water. No direct parallel is drawn here with the situation in Gaza, but many viewers will feel it. Letters are sent out to tell the students they’ll be suspended, which may seem tame in relation to what’s happening to some US students today, but highlights a slippery slope – whilst one student details how it is at odds with the university’s written policies on protest. In a meeting, a woman complains that shouting about the Infitada (sic) is clearly antisemitic behaviour, and later police will claim that they were there to remove those who had turned a peaceful protest into something antisemitic, trying to justify their use of flash bang grenades, rubber bullets and tear gas – but it is suggested that even they are not as unified in their feelings about the situation as they may seem.

There are heartwarming moments when we see something of the local community’s response to all this – and the joy of a Palestinian student who never thought that people from other backgrounds would stand beside her on this. “Bravery is very contagious,” she says. There is relatively little footage of Gaza itself, but we do see the destruction of al-Asraa and other universities, one Gazan pointing out that “any country’s greatest weapon is education.”

With so much arrayed against them, the encampments were never going to last forever, but Pritsker and Workman’s film suggests that they were still important – that they began the process of questioning and discovery, even in the absence of balanced media coverage, that is now beginning to change ordinary people’s thinking. Incisive and thorough, it is in itself a vital contribution to that process. One can only hope that it has not come too late – either for Gaza or for those Israelis who are engaged in their own still more obscured resistance, continuing to work for peace.

Reviewed on: 28 May 2025