Eye For Film >> Movies >> Riefenstahl (2024) Film Review

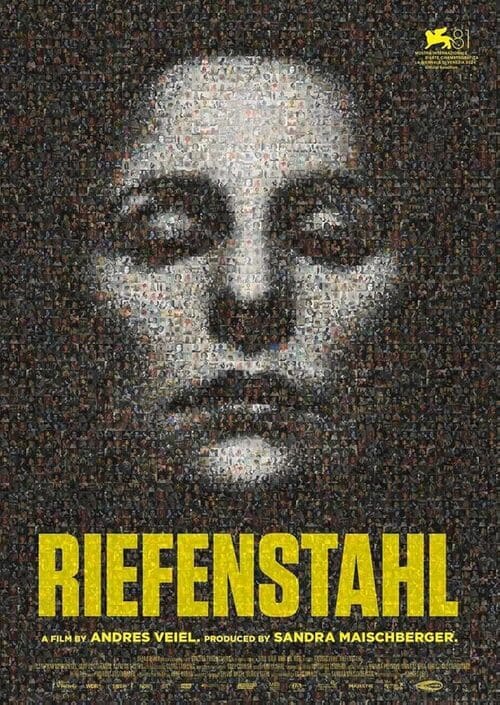

Riefenstahl

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

“For something to be remembered other things must be forgotten,” narrator Andrew Bird notes near the start of Andres Veiel’s thorough and psychologically fascinating and disturbing consideration of Leni Riefenstahl – a formidable directing talent, no doubt, but whose work is inextricably linked to Hitler and the Nazis. Selective memory was something Riefenstahl excelled at and, as a director, she was also adept at staying on message in the face of counter evidence, something which Veiel scrutinises throughout.

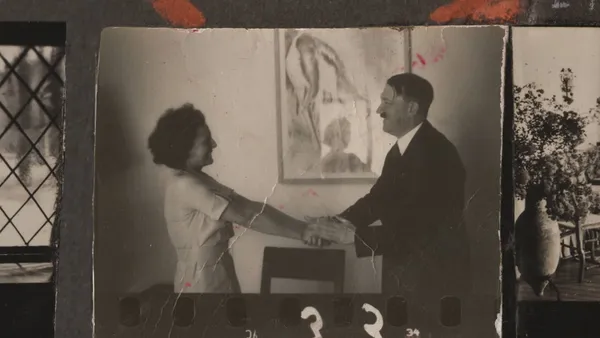

Riefenstahl was meticulous in terms of collecting her archive and Veiel draws on this extensively, along with interviews with the director, who unceasingly worked to rehabilitate her image throughout her 101-year life. Looking at her around the time she made her debut film, The Blue Light, she looks every inch the Hollywood starlet. Soon, however, she would be cosying up to Hitler, making the infamous propaganda piece Triumph Of The Will and her documentary of the 1936 Olympics, Olympia – which while fetishising bodily perfection in the Nazi style also established a lot of sports reportage grammar still in use today.

It’s hard not to feel repulsed watching her, in clips from 1993 film The Wonderful, Horrible Life Of Leni Riefenstahl, as she delights in talking through the various camera shots she used in Triumph Of The Will, tapping her hand up and down to the rhythm of the music and jackboot march. More telling is her attempts to reframe her own involvement with the Third Reich. She was never a member of the Nazi Party, which came in handy in terms of attempting to rehabilitate herself in the public sphere, but there is a wealth of material here to suggest where her sympathies lay.

When she asserts that Triumph Of The Will rally was all about “peace and work” and nothing so sinister as race theory, Veiel supplies clips that give the lie to it. Later, and perhaps most damning, we see her efforts to suggest Roma and Sinti children who were used as extras in Lowlands – having been selected for the purpose from an internment camp – lived happily ever after when they were, in fact, murdered in Auschwitz.

This is a rangy film that dots about a fair bit and sometimes raises questions it doesn’t seem interested in answering. It’s notable that virtually all her interview interactions are with men, for example, thanks to the time period. You can’t help but wonder what sorts of questions a woman might have asked her, particularly in regards to Joseph Goebbels, who she claimed tried to rape her twice. When she does come up against a woman, a housewife on a late night talk show, she finds, perhaps, her most formidable opposition. The film also prompts you to wonder about the life of Horst Kettner, her long-time partner, who was 40 years her junior.

Given Riefenstahl’s narcissistic obsession with appearance, it is interesting to note the way Veiel continually highlights her body language, which is often in contradiction to what she is saying. The complicity of many in West German society is also disturbing, including scores of letters and phone calls she received down the years supporting her. Riefenstahl’s ability to make her will triumph over that of others is evident to the last as she instructs a director on how to minimise her wrinkles. Veiel, in contrast, invites us to take a look, warts and all.

Reviewed on: 11 May 2025