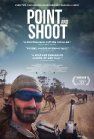

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Point And Shoot (2014) Film Review

Point And Shoot

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

What a difference a few months make. When I saw Marshall Curry's Point And Shoot at last year's Tribeca Film Festival - where it won the jury prize for documentary - the idea of people from Western countries such a America, Canada, France and Britain travelling to conflict zones such as Libya and Syria seemed an exotic notion.

Fast-forward several months and there have been several documentaries touching on the subject - #chicagoGirl: The Social Network and First To Fall to name just a couple - and the news is full of talk of the issue. In particular, how to stop would-be Jihadis/mercenaries becoming that in the first place, how to stop them travelling to conflict zones and what to do with them - not to mention what they might do to us - on their return to their homeland.

Point And Shoot offers a surprising - if problematically limited - perspective on the issue at the same time as questioning the nature of 'documentary' in war zones, not least because the would-be rebel here is white bread Baltimore boy of no explicitly mentioned religion, Matthew VanDyke, who heads to Libya as much because of friendship and the search for adventure as the urge to fight. Curry asks probing questions and edits sharply but the meat of the filming is first-person footage shot by VanDyke as, first, he embarked on a self-proclaimed "crash course in manhood" and, later, as he went to war. Curry wraps this footage in reflections from VanDyke - and his long-suffering girlfriend Lauren Fischer - looking back at the period of his life and considering what drove him to do what he did and what, if anything, he believes he has learned from it.

We meet him as a straggly-haired 28-year-old in his self-shot film, looking and sounding like a much younger man, as he talks about knives he has bought for himself and a camouflage jacket. His description of wearing one blade at his ankle jars strikingly with the fact that he struggles to flip another open. VanDyke is under no misconception of the young man he was and matter-of fact about it when questioned. "I was the only child of an only child of an only child," he says. "The centre of my family's universe".

What is most remarkable is that he ever left Baltimore. With obsessive compulsive disorder - triggered by spilt sugar and, particularly, rubbish bins and dirt - that also means he has a "fear of accidentally harming someone else" and a safe cocoon of family and intelligent girlfriend, it seems hard to imagine a less likely candidate. Facts which its worth considering when wondering what might have led up to an estimated 2,000 Britons leaving the country to fight with Islamic State (and doubtless other rebels). In VanDyke's case inspiration came, it seems, from little more than a childhood diet of adventure books, the shaggy shenanigans of Australian self-styled TV adventurer Alby Mangels (you can take a look at the dubious retro pleasures of his World Safari here and Fischer suggesting he was a "coward".

Heading to the Middle East, it quickly becomes apparent this a selfie-service adventure, with VanDyke frequently repeating shots to make sure he looks at his best in his "life story" and, as the idea of danger becomes a drug for him, we see him increase his risk-taking to the point where he is forced to cut short his meanderings. While in Libya, however, he meets "hippie" Nuri Fundas and founds a friendship that will go on to have a major effect on his life. Back in Baltimore, that ought to have been the end of the story, but when the uprising against the despotic Muammar Gaddafi VanDyke decided to return, camera in hand, as a self-styled "war correspondent" to help his friends. From here on in, by a series of baby steps - and a spell in solitary confinement as a prisoner of war (well-animated as a fluid mash of memory by Joe Posner) - he swaps his camera for a gun and joins the fight.

The most interesting questions are raised when we see rebels wanting to be filmed shooting guns or posing with them, a snapshot of the modern desire to post to Facebook even when faced with the possibility of being picked off by a sniper. But although there is a moment when VanDyke is unarmed - because he grabbed his camera rather than a gun - the idea of whether he might have been gravely endangering his friends' lives by his general naivety, ineptitude with Arabic and desire to film them is never mentioned.

This - and his incredibly tight focus on VanDyke, who is also a producer of the movie and therefore hardly arm's length - is where Curry's film falls down. While he is, inevitably, limited in terms of footage, like all the films I've seen on this subject - with the notable exception of Return To Homs - Curry reflects the conflict almost entirely from the viewpoint of the western outsider. There is no real sense of what the indigenous fighters feel about these incomers and the implication that the conflict ended with the fall of Gaddafi is simplistic in the extreme, given that turmoil in the region is a long way from over. It also seems inappropriate that there is no indication of where Fundas is now, as though the moment VanDyke left the country, nothing else mattered. As a study of one man's narcissistic motivations, Curry's film is taut but the bigger picture remains frustratingly out of reach.

Reviewed on: 09 Jan 2015