Eye For Film >> Movies >> Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio (2022) Film Review

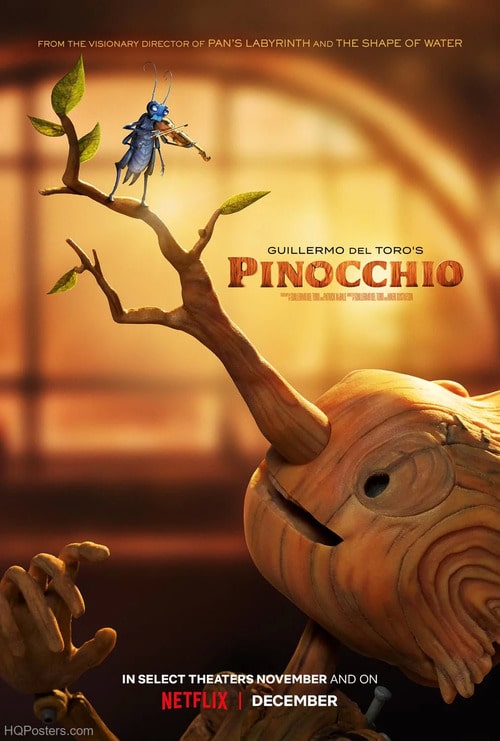

Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Since Carlo Collodi first published his account of a little wooden boy who wanted to be real, back in 1883, so many versions of the story have been created that it has become difficult to make a case for definitive one. Indeed, Collodi’s work itself owes quite a bit to the Greek myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, and to the automata of Hephaestus. Following hot on the heels of Matteo Garrone’s faithful yet mischievous 2019 version, it’s a more slimmed-down take on the original with no fox, no cat, and only the bare bones of the original story. In place of that material come a collection of feisty and fantastical phenomena which fans of Guillermo Del Toro’s work will recognise straight away.

Del Toro has a dream cast at his disposal, but perhaps the cleverest choice is David Bradley, who brings an emotional awkwardness to Gepetto which enriches this frequently underdeveloped character. The carpenter’s loneliness is explained by his having had a son, called Carlo, who died aged ten, and he is drinking heavily when we first meet him. The cricket (Ewan McGregor), meanwhile, inhabits a pine tree grown from Carlo’s treasured cone, and is made homeless when Gepetto, on an impulse, cuts it down to make his wooden boy, bringing the three characters together.

Retaining its rural Italian point of origin, Del Toro’s tale presents us with a somewhat sympathetic priest for whose church Gepetto has constructed a gigantic wooden Christ, but otherwise Christianity is out of the picture. It is a woodland sprite (voiced by Tilda Swinton, of course) who brings Pinocchio to life, and there is an underworld mythology here which resembles what we glimpse in Pan’s Labyrinth and Hellboy II: The Golden Army, but with the addition of semi-skeletal, card-playing black rabbits. This is a chaotic world in which bad things can happen with little warning (especially to the poor cricket), and in which there is plenty of human cruelty, but there is also kindness, and Pinocchio’s instinct to do what’s right (despite bouts of lying and spectacularly leafy nose growth) inspire those around him.

It’s a quality which is badly needed, as our young hero faces some formidable enemies. Firstly, the story has been relocated to the 1940s, there are the forces of fascism, carefully packaged so as not to display anything too distressing for young audiences but providing parents with a good jumping-off point for discussion. The local commander (Ron Perlman), father of Pinocchio’s friend Candlewick, is a man who retains a measure of kindness yet is gradually consumed by his ideology, and is drawn to the idea that Pinocchio could become the perfect soldier. There is also a cheerily unflattering appearance by Il Duce himself. Secondly, the forces of exploitative capitalism are represented by a carnie, not much changed from Nightmare Alley, though in this film Cate Blanchett has the rather less flattering role of Spazzatura, the fawning, gremlin-face henchmonkey of Christoph Waltz’s sinister ringmaster, Count Volpe.

All this detail fleshes out a world full of potential, but the plot still moves slowly in places and sometimes feels thin. There isn’t much emotional payoff until the final chapter, which comes with a downbeat, albeit realistic postscript – Disney this is not. It does, however, invite children to open up their imaginations and carry the story forwards for themselves.

There are various songs scattered throughout the film. They’re not very interesting in their own right, but they serve as a backdrop to playful action sequences which enable the animators to have some fun. Their work is strong throughout and, together with some excellent work from the sound team, makes this strange world easy to engage with. Objects which young viewers may not be familiar with, such as sea mines, are presented such that it’s easy to grasp how they work with no spoken explanation needed. Pinocchio himself is very noticeably a loosely bound collection of bits of wood, which are not hidden away behind clothing. This invites viewers to carry on believing in the magical nature of his existence, and in his personality, rather than forgetting about that and just accepting him as a boy like any other.

This is where the film is at its most interesting. Whilst previous versions have centred on the puppet’s anxious attempts to become a real boy, Del Toro deftly reframes that theme. What does it mean to be a real boy? Perhaps the answer doesn’t lie in flesh and bone. This is a film which is open to physical difference, which celebrates it, and which locates identity somewhere else. Pinocchio is defined not by how he is constituted but by what he does. This not only makes the story more inclusive, but it enables children to find a source of power within themselves in a world of air raids, giant sea monsters and constant relocation. It encourages them to be good, but it also invites them to rethink the rules.

Reviewed on: 27 Nov 2022