Although veteran Hungarian film director István Szabó is feeling “happy” and “honoured” about his presence at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, accompanying a restored version of his 1999 historical epic Sunshine as well as receiving a special tribute from Fipresci to mark the international film critics’ centenary celebration, he confides he harbours some misgivings.

Ensconced in a luxury hotel bedroom high up from the throngs on the Croisette he confessed: “Every time I see one of my films a few years on I always have this feeling about what I would have done differently and what would I have changed. It would be the same for you as journalist, looking back on article you had written even ten years ago. That said they showed me parts of it as they went along, and I was happy, and when I saw the finished version I was totally delighted.”

The restoration team at the Hungarian National Film Archive worked on the polished print with the original cinematographer Lajos Koltai, who made adjustments to the look of some parts of the film that would not have been possible under old technology. Besides Szabó other filmmakers whose works have been restored include: Zoltán Fábri, Miklós Jancsó, Márta Mészáros and Béla Tarr, many of whom also have been selected for the Cannes Classics strand of the festival.

Szabó has an enviable history at Cannes: he has appeared five times in Competition. He won the Best Screenplay and Fipresci prizes in 1981 for Mephisto, which went on to win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language film, and the jury prize in 1985 for Colonel Redl.

Against the background of cuts to cultural budgets in Hungary Szabó is at pains to praise the work of his producer Robert Lantos and head of the Archive György Ráduly. “They both did a lot of work to find the money and they did it together. These two people are responsible and I am very thankful. The two men had the energy and the digital restorer Anett Fulop had the knowledge and all three were vital to the end result.”

Ráduly said: “István’s films tell important personal stories, teaching us about our European history of the 20th century. Those who are not learning from the past, lack a landmark for the present and for the future. István’s films are perfect sources of knowledge.”

“Never say never” is a motto that Szabó at 87 is pleased to adopt. “Being a filmmaker is a kind of disease so you are always thinking about things you would like to be doing, but on the other hand there are some physical barriers at my age and you have to be aware of them. Your job is not only to create a story and invite actors to perform and represent some ideas and dialogues but it is also to give energy to some 70 or so people on the film team.

“You have to be on set one hour at least before the work for the day starts and shake hands with everyone and give them energy. And then at the end of the day you have to stay on for an hour or so to prepare for the next day. It is not enough to sit in a comfortable chair – it is a physical job and sometimes you can have some difficulties.

“You suggest I am like a circus master but I would describe it differently: you are the guy who is standing downstairs and you see these people flying through the air and you have to catch them or prevent them falling. And they have to know you are there downstairs and ready to catch them if they stumble. You have to create an atmosphere of trust and that you are the person they can trust whatever happens. That is why I am very happy I can still stand up and that you journalists are coming here to talk to me.”

|

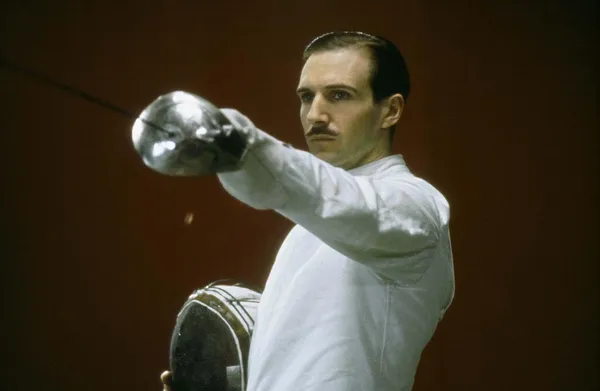

| Klaus Maria Brandauer in Mephisto. István Szabó 'If I found out only one thing about cinema it is that a living human face with emotions that change can only be shown in the cinema' |

“And then after a year of being in love with theatre I got accidentally a book about cinema written by Béla Balázs, The Visible Man, about silent film. Reading this book it was like a light to understand that film is more interesting than theatre. I have to tell you, it’s ridiculous but it was enough for me to go to film school to learn the profession. I went at 19, for five years. Then I became an assistant director and at the same time I did short films, and they were successful and I got my first feature film possibility when I was 25. Today a young film-maker’s age is around 40 to 45.”

With a 1961 degree from the Budapest Film Academy, Szabó blossomed into an extraordinary storyteller. In 1965 he made Age of Illusions (Álmodozások kora), before reaching international acclaim with Mephisto. As a director he was hailed for his “humanist gaze upon the wounds of European History.”

He believes that Sunshine which chronicles the saga of the Sonnenscheins, a Jewish-Hungarian family confronted with the changes that are taking place in Central Europe over about a century, following their social rise, their disappointments and their struggles to survive the devastating effects of anti-Semitism and totalitarianism, should hold up to contemporary consideration.

Szabó and his co-writer, playwright Israel Horovitz, mirror every upheaval in Hungarian life, particularly the three generations of scions played by Ralph Fiennes. The constant mixing of personal and political turmoil has a soap operatic effect.

|

| Head of the Hungarian National Film Archive György Ráduly: 'István’s films tell important personal stories, teaching us about our European history of the 20th century' Photo: Hungarian Film Archive |

Szabó was a founder member of the European Film Academy in 1989 along with such luminaries as Ingmar Bergman and remains active. “We had no idea what would be the future of European cinema but it seemed to be in danger. Bergman and 40 filmmakers signed up to advance the interests of the European film industry.

“I still have optimism and hope but German and Italian films hardly exist any more compared to previously and there are few Czech or Polish films. I understand that Covid changed things and people are watching television more. And series usually are well made and can involve good actors, but I love cinema. We have to tell our stories differently, and we have to reach out to a bigger audience and then we have to re-educate them that cinemas are the right surroundings in which to see films to best advantage.”

Does he have a message to impart through his work? He chuckles amiably and responds with a quote from producer Samuel Goldwyn who has been credited with saying: “From Western Union you get messages. From me you get pictures.”