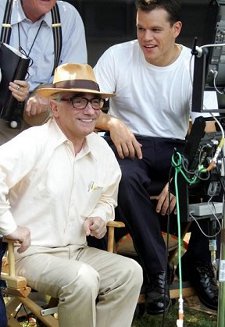

Martin Scorsese and Matt Damon on the set of The Departed

The legendary Martin Scorsese spoke candidly about his career as a director of feature films, documentaries and his efforts in film preservation at a special Alfred Dunhill BAFTA A Life In Pictures event in London last weekend.

At 68 years old and with an encyclopedic knowledge of film and an abundance of energy and enthusiasm, Scorsese can claim to have created some of the most remarkable films of all time. In his trademark machine-gun patter, the director reflected on the key moments in a career so rich and long that he was under time pressure throughout.

In the early 1970s, having turned away from the priesthood and served an apprenticeship under exploitation director Roger Corman, Scorsese went on to craft a series of films, in partnership with leading man Robert de Niro. Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, King Of Comedy and Goodfellas have all come to be seen as defining works, not just of his career, but of modern American cinema.

More recently there have been higher-grossing pictures which have seen Leonardo DiCaprio step up as the director's new muse - The Departed, The Aviator and Shutter Island. There has also been a ongoing and prolific Scorsese 'sideshow' in both documentaries (such as The Last Waltz, Shine A Light and No Direction Home) and promoting under-appreciated or forgotten works of cinema, such as the recently re-released career-crippling Michael Powell thriller Peeping Tom.

Born in the rough neighbourhood of Flushing, New York in 1942 to Italian American parents, Scorsese recalls being a sickly boy, whose asthma meant his parents were protective of him: “The idea was I shouldn't run or laugh. All they could do for me was school... and movie theatres. My parents didn't have a culture of books, so instead there were films on TV and in the theatres.”

This exposure to cinema unlocked a passion in the small boy. Scorsese fondly recalls being taken to see Roy Rogers films by his father, and being affected by more bolder and exotic fare such as King Vidor's Duel In The Sun. “I remember watching Duel In The Sun, which was condemned by the church and lambasted by the critics. My mother used the excuse that I liked westerns to take me to see it. I liked it but it was very disturbing to me, but that explains much of what I've done since.”

After leaving seminary (“I was asked to leave, I had started to think I didn't have it in me, so maybe that energy went into cinema”), Scorsese attended Cardinal Hayes High School in The Bronx, before graduating from New York University and quickly moving into NYU's master's program for film making in 1966. It was here, working on his masters degree, that he would make several short films and meet later collaborator (and Mean Streets star) Harvey Keitel.

By now he was almost perfectly placed – able to be exposed to a rich kaleidoscope of films from all over the world in the heart of the one of the most culturally 'happening' cities on earth. “French and Italian New Wave cinema, new British cinema, these things just cut through all other things that were playing,” Scorsese remembers.

|

| De Niro and Keitel in Mean Streets |

It was a heady time to be in film making: “The village [Manhattan] was a different world. Just six blocks away from where we lived. And I was seeing a lot of foreign films - there was the beginnings of something. I didn't recognize then that the Hollywood system was breaking down. There were directors like Shirley Clarke and John Cassavetes – it soon became clear you didn't need the traditional studio system.”

When discussing Mean Streets (1973), Scorsese is quick to praise director Roger Corman who hired him two years earlier in Los Angeles, where he worked on the Depression-era crime thriller, Boxcar Bertha (1972) . “Roger Corman taught me how to make movies. You need to plan ahead, I learned that from Corman and his group, so in a way they created Mean Streets.”

After watching a short extract of the film itself - the famous bar scene where De Niro's playboy Johnny is confronted by Keitel's Charlie about his constantly missed payments to the local mob (all squeezed in on the last day of shooting) - Scorsese expounds on his distinctive use of musical cues, high-speed shots and intense lighting, all of which are now conventions particularly associated with him. “It all came from the influence of real life in NYC,” he says, “ I saw all this life from the third floor window of our block, the decline of Fifties rock and roll, Russian, French and British Cinema, the British music invasion, Vietnam, JFK, girl groups. I saw it in red and I saw it in high speed.”

Scorsese was also becoming involved in documentary work at this time. After watching an extract of Italian-American, a made for TV documentary from 1974 that is set in and around the Scorsese family apartment, the director recalls how he wanted to use a more unusual narrative structure to depict modern Italian American life in New York when he was given the project. “I was asked to do it based on Mean Streets, but I wanted to do it in a different way, like showing a dinner at my parents in their apartment on Elizabeth Street.”

This decision meant a more intimate approach to the subject matter, with the documentary putting viewers right in the living room of the brilliantly idiosyncratic Scorsese parents. A great deal of time is given over to the importance of food and the meal to an Italian-American family, particularly the sauce. “The sauce would probably start the day before,” Scorsese recalls, “and there was lots of discussion about the menu. People would come by the apartment all the time, a constant flurry. So the sauce really had to start the film.”

|

| Ellen Burstyn in Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore |

Following 1974's Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (to date his only female centric film) Scorsese fashioned, again with Robert De Niro, Taxi Driver (1976) out of Paul Schrader's script, cementing his reputation as a key member of Hollywood's new Golden Age. Scorsese had considered filming it in black and white, though ultimately the film was shot so it felt drenched in a dream-like aura of colour. The shooting was characterised by improvisation in key scenes - another trademark of the Schorse/De Niro team - and intense time pressure (“We were always under that incredible pressure”).

It was a hot and difficult shoot, the director remembers: “It was one tough summer; NYC was declared bankrupt, headlines in the papers were saying 'New York can go to hell'.. Yeah, it was horrible, but it was always that way to me. I'm always a little careful, there's always a flinch. Even today I never go to Central Park!”

To Scorsese, Taxi Driver is not just a Vietnam war film, though that war looms large in the background of the character of lone-gun Travis Bickle, it is a film “about being alone, having ideals smashed, being disaffected. Today it could be Afghanistan or Iraq. The script is Paul's God's lonely man story.”

|

| De Niro as Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver |

Scorsese actually thought at first that he would just be recording the show for posterity, but over time “the project just got bigger and bigger, so I thought about doing it in 35mm.” The planning was meticulous, but Scorsese recalls how the actual seven-camera shoot of such a major event sometimes seemed to be slipping out of his control.

After watching a clip from the film of the Muddy Waters' set, Scorsese recalls the happy accident that allowed it to be captured on celluloid at all. At one point in the shoot that night, all the cameras except cinematographer László Kovács' had shut down, just as Muddy Waters was going on stage to perform Mannish Boy. Kovács had not heard the orders to stop filming simply due to his taking his headphones off out of frustration. As a result, Scorsese was luckily able to capture the iconic song.

|

| Scorsese has made a string of music documentaries, including The Last Waltz |

After watching a montage clip of the fight scenes in Raging Bull, Scorsese recalls: “I broke the fight sequences up like bars of music, into blocks. Each fight is presented in a different way.” Scorsese used rings stretched to three or four times the normal size, adjusted the speed and apertures of the cameras, and worked with sound editor Frank Warner (who mixed the audio track using such odd sounds as elephant and tiger roars) to shape the distinctive and violent style of the bouts De Niro's character wades through.

Speeding through the Eighties (which has often, perhaps unfairly, been regarded as a creative lull, though it contains another of his De Niro collaborations The King of Comedy), Scorsese comments that, unable to initially make the controversial The Last Temptation Of Christ earlier in that decade, his experiences with making After Hours (1985), and Colour Of Money (1986) helped him to “go back and learn how to do it all over again.” The critical success of the Paul Newman vehicle Color Of Money especially helped him regain the trust of the new bosses who were running Hollywood. “It showed I could do something on time and on schedule.”

|

| Pesci and Liotta in Goodfellas |

Watching a clip of the now iconic tracking shot sequence of Henry Hill's (Ray Liotta's) entry into the Copacabana lounge with his date Karen (Lorraine Bracco) in tow, Scorsese recalls “that was where all the deals were made in NYC, upstairs in the lounge, only the tourists went downstairs. So we wanted to take the audience all the way up to the lounge front row.” The result is a truly remarkable technical feat of cinematography, tied with diagetic use of the 1963 hit song And Then He kissed Me, that enhances and reflects the film's primary concerns with the glamour and violence of mob life.

Jumping forward to 2005, Scorsese muses over his motivation to take on the Bob Dylan documentary No Direction Home when the Dylan archives were offered to him by Dylan's manager Jeff Rosen. “I liked the shape changing, the way Dylan's eyes moved back and forth, and I was also interested in the idea of Judas the betrayer [referring to audience hatred of Dylan seemingly moving away from his folk roots].” Scorsese didn't get to meet Dylan and was limited to collating film up to 1966, but that was fine with him as “I wasn't looking to do an expose - the truth about the man and such. Its a complex issue and you have to find it in the footage.”

Appropriately ending with a screening of one of the stylised dream-sequences from his 2010 psychological thriller Shutter Island, Scorsese comments on the perceived critical reading that this film is his own personal homage to the noir thrillers of the 1940s and 50s.

|

| Ruffalo and DiCaprio in Shutter Island |

Fascinated by the original Dennis Lehane novel's maze-like structure, littered with red herrings and dropped clues, Scorsese sprinkles Shutter Island with distinctive hallucinatory sequences and editing choices that betray the tortured mind of main character Teddy Daniels (Leonardo DiCaprio) and raise the issue of the reliability of the main character's perceptions and ultimate sanity. “What is real? I've often seen things that weren't there, due to being tired or wearing glasses. All these scenes deliberately have a number of levels to them.”

As for the future, Scorsese confirms that he and De Niro are still on course to re-team in The Irishman, which is based on the novel I Heard You Paint Houses by Charles Brandt, and centres on union official-turned-hitman Frank "The Irishman" Sheeran. Scorsese collaborator and Gangs Of New York and Cape Fear screenwriter Steve Zallian has penned the script. All are now trying to fix a date to start work. Coming before that though will be Scorsese's first 3-D project, Hugo Cabret, out in cinemas in late 2011 (read a review of that here).

Though he shows no sign of slowing down, Scorsese admits that he worries that with Hollywood's focus on weekend grosses, maybe now there is no real sense of value in cinema. Before leaving, he muses that the period of cinema he grew up with and which so enriched him might come to be seen “like Italian opera or guitar solos by Clapton - a golden age. We have this love for that period, but it's gonna change”.