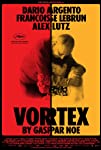

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Vortex (2021) Film Review

Vortex

Reviewed by: Levan Tskhovrebadze

Gaspar Noé’s latest feature Vortex (2021) - a distressing immersion into the emotional vortex of dying elderly couple - has surprisingly naturalistic and metaphysical, eerie quality. As with Enter the Void (2009) Noé takes a cinematic monograph of death, observing the last days of an ex-psychiatrist (Françoise Lebrun), who is suffering from dementia and a film scholar (Dario Argento) with a history of heart failure. Vortex is full of intellectual passages and references to classical films however the cinematic approach is fresh. It’s the most restrained and yet audacious, unadorned and still intelligent picture the Argentinian auteur has made.

Most of the critics and the audience have suggested Vortex is a change in Noé’s direction of interest as it revolves around a different peer group than his previous work. However, the social and cultural atrocities, abnormal drug addiction and socially alienated people are still in the plot while the son of the couple Stéphane (Alex Lutz) is like a ghost from the director’s earlier cinema. Noé pulls off a quasi-documentary move by naming the two central characters (Dario and Françoise) after their off-screen selves. Another documentary approach is a split screen. The director previously experimented with this in Lux Aeterna (2019) but in Vortex, it’s more than experimenting with form and has an essential and insightful value.

In the opening 1:1 ratio camera in the centre of screen is pointed to a bright blue sky and moves vertically downs capturing the exquisite little balcony of the couple’s home. This crane shot manoeuvre augurs the mystical premises that will be revealed by the end. Dario and Françoise enjoy an evening meal and a glass of wine with the camera now moving horizontally sticking to the wall. After a little while, Françoise Hardy invades the screen with a video clip of the 1960s classic Mon Amie la Rose (My Friend Rose) a delightful melody and a melancholic poem about mortality. The couple goes to bed, and that’s when the screen splits.

Françoise’s dementia evolves day by day as Dario’s frustration about life and work grows (he’s writing a book about dreams and cinema with the working title Psyche). Although Stéphane has his own existential, financial and family crises, still he endeavours to be present in his parents' vortex of ageing. Because of Françoise’s professional history, she prescribes her own and sometimes Dario’s pills and it comes off as an unusual and excessively dangerous dimension of drug addiction.

Noé comes from a generation of filmmakers classified as New French Extremity, whose films stand out for the transgressive aesthetics, “visceral horror” (Alexandra West), and gruesome carnal desires, so filming the issues of aged people seems quite off-beat but Vortex presents a more extensive recognition of the subjects the director has always been concerned with.

Before Vortex Noé portrayed bodily horrors, physically violent imagery and the evils of human beings while here he shows the monstrosity of brain, mental abuse and the cruelty of life. If Irreversible (2002) represents a 10-minute rape scene Vortex displays almost seven-minute heart attack sequence. If in Climax (2018) a young dancer puts drugs in sangria on purpose and people go insane, here an elderly lady with Alzheimer’s takes the wrong pills randomly destroying her cerebrum. Enter The Void offers a point of view of dead person’s floating spirit inspired by the Tibetan book of dead while Vortex presents a disturbing venture to death implicitly influenced by Carl T Dreyer’s 1932 waking nightmare [film id= 14628]Vampyr[/film].

Noé’s appreciation for Dreyer was initially disclosed in Lux Aeterna creating a postmodern, neon-lit portrayal of martyrdom with Charlotte Gainsbourg’s embodiment of Joan of Arc. In Vortex, Noé took more extensive account of Dreyer, encompassing the Danish auteur’s essential interplay between “forces, styles, or schools” (Paul Schrader). They are Kammerspiel, transcendental and expressionist styles however Noé adopts the extremity of realism instead of expressionism.

The extremity of realism comprises a combination of words concluded by two cinematic trends and schools: New French Extremity and Social Realism, that are relevant for Vortex but clarifying this term needs a deeper penetration and more systematic study than just an essay about the film. Nevertheless, Kammerspiele and transcendental style are more interesting right now.

Kammerspiele a term coined by Walter Schobert in 1931 possess roots in the tradition of theatre. The exact English translation of the German word ‘Kammerspiel’ is ‘Chamber Play’ advocating an intimate theatre with few characters, a single location and with simple dialogue, usually featuring drama between family members. This practice of filmmaking, originally embraced by German directors from late 1920s to early 1930s, was one of the defining techniques of Dreyer’s pictorial representation. As Schrader suggests “Kammerspiele embodies a simplicity of scenic means, a refusal to use declamatory effects, a systematic realism, rigorous action, and a measured symbolism.”

Hence, by locking the dying couple at home with a split screen Noé sketches a hyper-real design of Kammerspiele to address Dreyer. Furthermore, the Argentinian auteur explicitly communicates with Dreyer’s phantom when Dario watches the appalling finale of Vampyr. In that scene of the Danish classic, the camera identifies with the view of a dead man taken by the coffin. At the same time, on the other side of the split screen, mentally mazed Françoise is wandering around rooms evoking a chilling sense that we are actually watching another corpse detached from its soul. The aesthetic of intimate theatre in Vortex is so obvious even from the beginning when the routine of the couple is disclosed: waking up, brushing teeth, bathroom time and etc. while the transcendental style needs to be scrutinized in abundant layers.

To begin with, Kammerspiele is a perfect place to experience the transcendent because the first step of transcendental style is “the everyday: a meticulous representation of the dull, banal commonplaces of everyday living” (Schrader) and chamber play offers all of those cinematic levels. However, the specific point of transcendental style is to express the Other in form.

Here, the encounter with the Other occurs both verbally and visually. From the very beginning, the camera movement and the perspective of the frame designate the so-called God’s Eye. The couple says repeatedly that "life’s a dream within a dream". Dario explains the movie theatre experience as being in a bed and dreaming because it’s dark and you don’t contact anyone. So with all those things, Noé aims to contemplate the Other on screen and the outcome is devastating.

In Lux Aeterna, split screen is just an experiment with formal assets while in Vortex it considers both stylistic and substantial merit. The pictorial composition of the ageing couple in different frames designates their emotional detachment - we follow their routine separately and together at the same time. Their spatial perception is so different it’s like as though they are talking to each other by video call. When the camera sticks to the wall in the beginning the director hints that the screen represents a wall itself. In Vortex, the screen becomes something like a church wall because we practically contemplate icons, frescoes and waking hallucinations. This technique acquires psycho-mystical depth both physically and thematically. From time to time leading characters cross each other’s frames and whoever is in the left frame is in danger.

In the fullness of time Vortex with its dreamlike exposition and nightmarish narrative is a dazzling picture moderately haunted by the phantom of Dreyer. With its abnormal content and manner, Noé contemplates death and, equally, challenges the audience to look in the eyes of death. Once Roger Ebert wrote about Carl T Dreyer’s Ordet that it’s a difficult film to enter but once you’re inside it it’s impossible to escape and the same goes for Vortex, too.

Reviewed on: 04 Aug 2022