Eye For Film >> Movies >> Yellow Letters (2026) Film Review

Yellow Letters

Reviewed by: Edin Custo

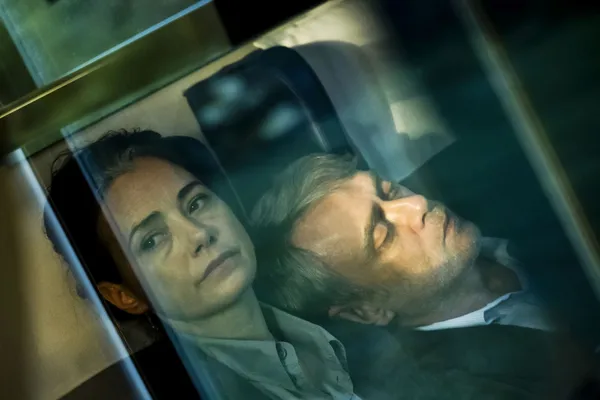

All of Germany becomes a stage in İlker Çatak’s Yellow Letters, his first Berlinale Competition title following the 2023 Oscar-nominated The Teachers’ Lounge. The premise follows a Turkish liberal intelligentsia family, Aziz (Tansu Biçer), a university professor and playwright, and Derya (Özgü Namal), a national-theatre actress, as they fall out of favour with the state-funded cultural establishment. The formal conceit is blunt. Berlin plays the part of Ankara and Hamburg plays Istanbul, and Çatak doesn’t even pretend otherwise, announcing locations in big red onscreen text.

Aziz’s trouble begins when he nudges his students toward a left-wing protest against the state, one that includes LGBTQ+ rights among its causes. He is suspended, then pulled into a criminal case through selective social-media evidence, charged for speaking against a nameless president. Derya, in solidarity, challenges the theatre that stages Aziz’s play and soon loses her own footing. Under pressure and surveillance, the family relocates from their comfortable life in Ankara to Istanbul, moving in with Aziz’s mother, as the drama shifts from public dissent to private containment.

The film sharpens when it tracks how the fall from public grace reorganises the couple’s private life. Derya becomes the pragmatist, less interested in maintaining a posture than in surviving the consequences of it, flattening their horizon to something like triage. “Now our only dream is getting through the day,” she says, a line that lands not as melodrama but as the first honest recalibration of their lives. Aziz moves in the opposite direction, doubling down on the identity of the persecuted intellectual. He writes again and pushes to mount Yellow Letters in a small Hamburg-as-Istanbul theatre run by a friend, not as an act of resistance so much as a bid to keep a certain mirror in place, a pseudo-public where he can still be witnessed as significant. The system outside remains unmoved by these gestures; the audience he seeks is consolation, not confrontation.

When that consolation is punctured, Çatak lets the real politics leak through the domestic ones. Aziz’s ego does not merely bruise, it lashes out, and the language of ideals collapses into ownership. In a furious turn he tells Derya he “made” her, that she would be nobody without him, and the film’s earlier talk of courage and principle is revealed as something he has been using to shore up a more archaic authority at home. The director’s neatest move is to make that rupture unmistakable: older systems of domination always show their seams, and here they surface at the precise moment the protagonist can no longer control how he is seen.

What the narrative wants to test is the cost of principled resistance when you have a child to protect. The couple’s public confidence, their “picture-perfect” cultural success, cracks under material precarity, and older dynamics surface, not least around gender, compromise and what counts as bravery when the consequences are no longer abstract. That’s the strongest thread the film has, and the one it too often interrupts with its own gimmickry.

The Germany-as-Turkey cosplay is, on paper, intriguing. Çatak’s own biography makes the transposition legible, and so does the everyday visibility of Turkish life within Germany. Yet the masquerade keeps giving itself away. German inscriptions hang in the frame like loose threads, from a university door marked “Gott helfe” (“God help us”) to a courtroom intoning “Im Namen des Volkes” (“In the name of the people”). The seams aren’t just visible, they’re almost invited, which raises the question the film seems to flirt with without committing to: is the disguise there to criticise Turkey at a safe distance, or to let Germany, and the West writ large, stand accused too?

That ambiguity becomes sharper when the opening protest includes Palestinian flags, an image that inevitably recalls Germany’s own recent clampdowns on pro-Palestinian demonstrations. And the German title, Gelbe Briefe, points back to the country hosting this masquerade: in Germany, court and other official legal notices often arrive in a distinctive yellow envelope, the kind that turns anxiety into a deadline. The film is at its most pointed when it lets that administrative dread hang in the air.

Still, for all its self-awareness, Yellow Letters can’t fully escape what it mocks. In sneering at the melodramatic reflexes of Turkish TV soaps that Derya is pushed toward, it slides into similar vices. There is food for thought here, and some bold choices, but the question that lingers is whether those choices clarify the political trap – or merely decorate it.

Reviewed on: 17 Feb 2026