Eye For Film >> Movies >> Two Seasons, Two Strangers (2025) Film Review

Two Seasons, Two Strangers

Reviewed by: Jeremy Mathews

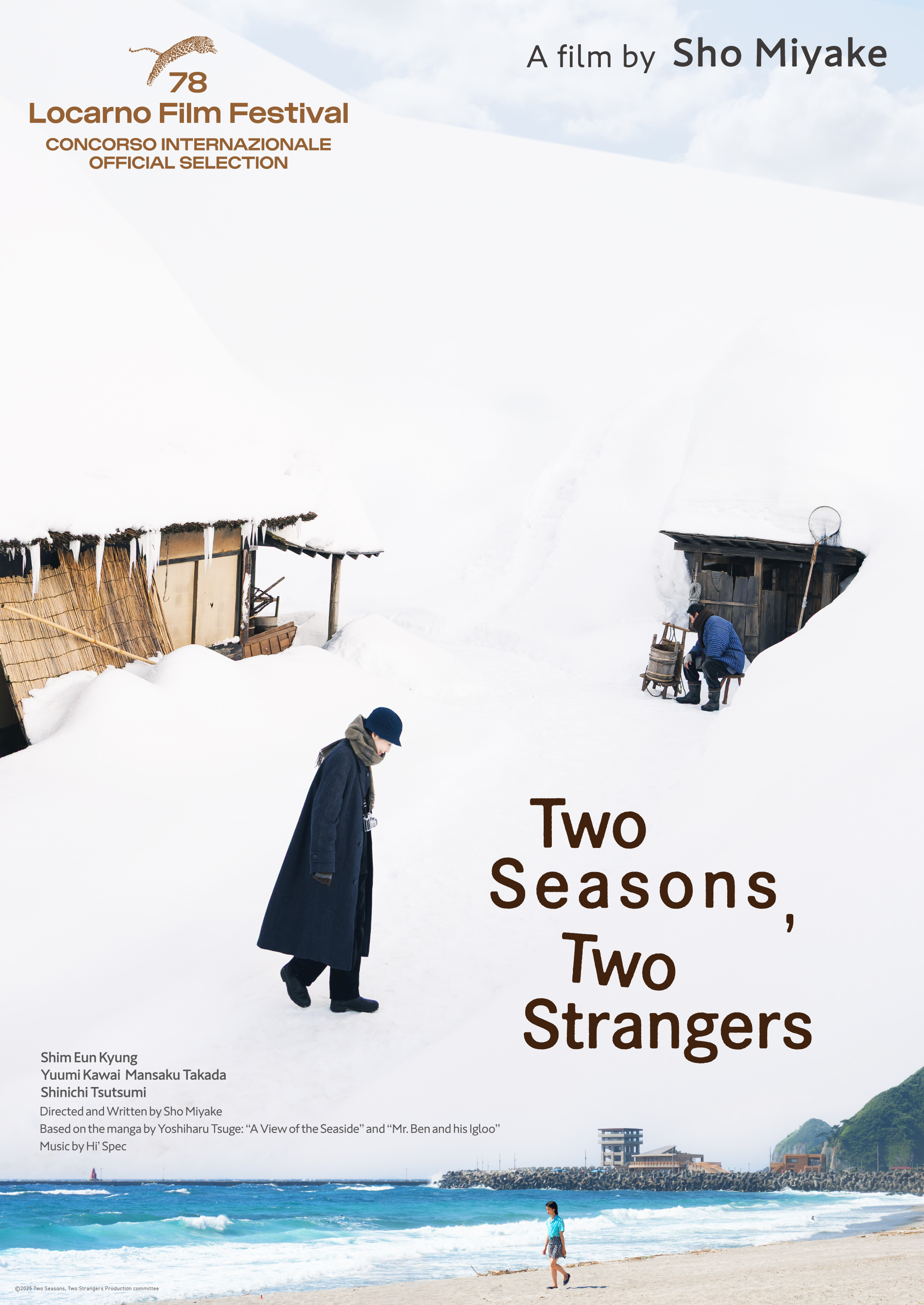

The impact a person can have on another’s life doesn’t always correspond with the amount of time they spend together. A connection can provide a much-needed moment of clarity or empathy, even if it only lasts a few days. Sho Miyake’s Two Seasons, Two Strangers studies this premise in a quiet but poignant way, showing both the discovery of youth and the regret of age in a deliberate but efficient one-two punch, set within two small Japanese locales with modest tourist appeal.

The film, which won the Golden Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival, presents two stories, one after the other, that are connected thematically but not by character or narrative – notwithstanding a clever framing device that allows the first story to flow seamlessly into the second. We recently saw the same sort of free-flowing anthology in Lisandro Alonso’s 2023 triptych Eureka, which leaps across time and place to present different stories of the American indigenous experience. Miyake’s film feels less expansive than Alonso’s, opting instead for two personal tales about fleeting friendships, one of youths in summer, the other between two adults in different stages of their lives, set in a small town during a cold, snowed-in winter.

The stories come from two 1960s mangas by Yoshiharu Tsuge, A View Of The Seaside and Mr Ben And His Igloo. The first depicts two young adults, Natsuo (Mansaku Takada) and Nagisa (Yuumi Kawai) in the dying days of summer in a small seaside village. Natsuo is visiting family and feeling aloof in a town of foreign tourists. When he meets Nagisa, she projects a familiarity with the area, though what we see of her life suggests she’s a drifter. The two don’t bond over much held in common, but a secluded beach gives them a certain kinship with each other and the rhythm of the waves.

In the way a film might frame its story’s source material by showing book pages flipping or a stage curtain opening or a character writing in their journal, Miyake introduces this summer story by showing the most obvious yet unexpected source material: a screenplay. A woman sits in her apartment and writes it by hand with a pencil. Miyake even makes sure we don’t forget the framing device, by popping out of the story just to show the woman silently continue to ponder the story.

But it’s not until the first story ends that the framing device really goes into meta mode. Our film-within-a-film is no longer in the writing process, and the content we’ve been watching isn’t a hypothetical film on paper, but an actual one on screen. It just finished screening for a film class, and our writer, Lee (Shim Eun-kyung), participates in a Q&A for the now-finished film with the director. The two awkwardly sit through questions, comments and critiques from the film class.

While any festival-going film buff has sat through some tedious Q&As, it’s an unexpected twist to suddenly watch people share their thoughts on the film you just watched while you’re still watching it. A student shares that he didn’t get the point. The professor talks about how it’s more experiential than cerebral. Our hero writer says that while watching, the thought crossed her mind that she’s not a very good writer. The move could have come off as masturbatory, but Miyake pulls it off in a gleefully cheeky fashion, simultaneously sending up the inadequate process of talking about film while transitioning to the film’s second story.

Shortly after this screening, the funeral of Lee’s old professor eventually leads her to wandering a snow-covered mountain village where all the modern hotels are full. That’s how she meets Ben (Shinichi Tsutsumi) at his inn. While words like “traditional” or “rustic” might suggest old world charm, the reality is that the inn is basically a big living room where Ben also sleeps. Fortunately, there aren’t any other guests, so at least Lee only has to share her sleeping quarters with the owner.

During her time with Ben, Lee finds herself irresistibly intrigued. His beautiful koi fish in a random metal canister; his eagerness to go make mischief in the middle of the night; his refusal to talk about his recent divorce – all these things are strange and some of them reckless, but she can’t help but draw herself into his story.

The summer-winter dynamic may lean a tad on the obvious side, but the structure primes us to meditate on the way friendships form during different stages of life, and which lives they’re most likely to change. And, because Lee reveals in the Q&A that she developed the seaside story for the director rather than it coming from a personal experience, it obfuscates just how much of that story is part of her. And the story she’s stalled out on was about ninjas – also not personal. Meanwhile, as she looks upon the remnants of Ben’s old life, she contemplates a new story (a story Ben thinks might help drive traffic to the inn, even if the details are too painful to share with his new friend).

Miyake tells both stories with a pensive, meditative quality, capturing the slow-moving nature of his settings and the quietude of his characters. It’s the kind of thing that sneaks up on you. Maybe you don’t think you care much at all, but then you’re hooked, like someone who just realised the stranger they’re talking to is the most interesting person they’ve ever met.

Reviewed on: 10 Sep 2025