Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Gas Station Attendant (2025) Film Review

The Gas Station Attendant

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

“Humanity is fundamentally a story of migration,” reads the intertitle quote from Moroccan-American writer Laila Lamia at the start of Karla Murthy’s intimate documentary. Migration is also fundamental to Murthy’s life, although she is first-generation American who has always lived in the US. Her father, Shantha, began his own story of migration at the incredibly young age of ten. His first step may have only been from countryside to city but it may as well have been an ocean in the sense that it would be decades before he went back. As a teenager, he would move even farther, after his path crossed that of a couple from Texas who on what seems almost to have been a whim – but which also speaks to Shantha’s charismatic character – decided to sponsor him to join them in the US.

This piece of luck did nothing to diminish Shantha’s striving attitude, which was a lifelong driver within his world as an almost exhaustive list of jobs and business opportunities were taken and, just as frequently, lost. A life that is, in many ways full of things lost and found, we also hear how he met and married a Filipino migrant, Karla’s mother, and what happened subsequently.

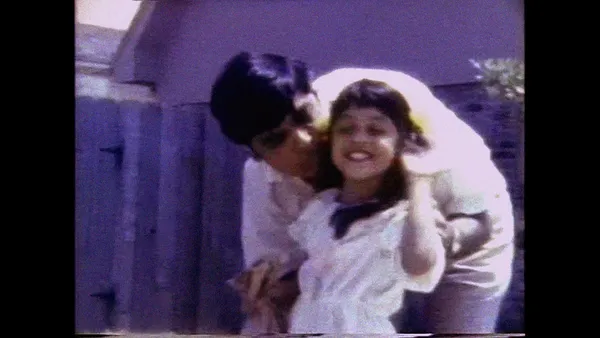

Karla offers an impressive kaleidoscope of family life in the Murthy household with her large clutch of siblings. Along with a lot of home video shot down the years, we are also able to hear a considerable amount of Shanta’s story first-hand as, during late night phone conversations she recorded when he worked as a petrol station attendant to help make ends meet, he reminisces about his childhood. The director frames these with dreamlike imagery, using archive and also shots of someone running, an apt metaphor for her father’s seemingly limitless energy.

There has been a trend in recent years for filmmakers to dissect their relationships with their relatives, including the likes of Lynne Sachs’ Film About A Father Who, Nira Burnstein’s Charm Circle and Asmae El Moudir’s The Mother of All Lies. The Gas Station Attendant differs from these in that, although Karla doesn’t dodge the more difficult side of family dynamics – not least the secrets her father kept from her – she doesn’t lean into the negatives. Instead, she uses her father’s story as a doorway into the experience of migrants and their children more generally, examining the psychological positives and negatives of moving your life to an entirely new situation. Beyond the fact that Shanta’s story is remarkable in its own right, this is a reminder that behind every person who is labelled a “migrant” there is a very specific personal story. Karla highlights how reductive the world can be with a shot of Apu from The Simpsons – and for more on how that has shaped many first generation American’s experiences, The Problem With Apu is well worth a look. Karla also broadens out her theme to consider how her own attitudes towards her parents have shifted as she had children of her own.

Universal ideas interlock with this personal and resonant story. When Karla says, “It’s a time-travelling gift to see your parents in the places that made them,” it may be referring to returning to her mother and father’s homelands but it is likely to strike a chord with anyone who has ever taken a physical trip down memory lane with a parent and seen their memories spring to life in ways they never can in other situations.

Reviewed on: 21 Jun 2025