Eye For Film >> Movies >> Peter Hujar’s Day (2025) Film Review

Peter Hujar’s Day

Reviewed by: Jeremy Mathews

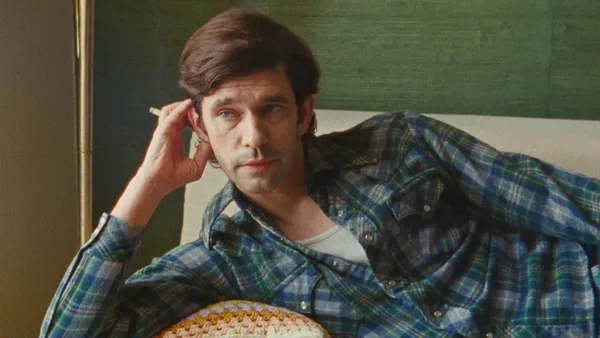

Every so often, a film needs to remind us that the rules aren’t really rules. Sure, it’s probably a bad idea to make a film that consists entirely of two characters in an apartment talking, especially if one guy does 95 percent of the talking. But if that guy is played by Ben Wishaw in a career-best performance, you might end up with a gem.

Writer/director Ira Sachs adapted Peter Hujar’s Day from a transcript of a 1974 interview with photographer Hujar by writer Linda Rosenkrantz in her New York City apartment. Rosenkrantz planned to make a book featuring a series of artists recounting what they did the day before each interview. She never finished it, and the recording of the interview was lost. (She released a standalone book on Hujar’s day in 2021.)

Watching this transcript brought to life, it’s clear that Rosenkrantz was onto something with her concept. There’s a certain magic in thinking about a life not only in huge accomplishments, but in naps, dark room work and thinking about whether you really want to join someone for dinner. In some ways, the day in question is far from ordinary. Hujar name-drops icons like friend Susan Sontag and Allen Ginsberg, whom he photographs for the New York Times that day. But he also talks about Chinese food and how high the prices of the things he bought were (which, of course, all sound ridiculously low 50 years later).

Sach’s resists the temptation to flashback to the day being described, instead making the conversation the focus. In doing so, he makes the film less about the day than the recollection of it.

Wishaw is an absolute wonder, delivering the conversational, sometimes stream-of-consciousness dialogue with a constantly engaging, almost hypnotic cadence. When the film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, Wishaw said a musician friend compared him working with that dialogue to trying to memorise someone else’s improv – no easy task. But Wishaw somehow finds the rhythm and the meaning in the phrasing. Rebecca Hall has considerably less dialogue to worry about as Rosenkrantz, but handles the role with a combination of confidence and observation, prodding and prompting to get remarkable responses.

Sachs isn’t overly concerned with realism or the literal passage of time, favouring visual engagement over realism. Over the course of the 75-minute conversation, a whole day passes on screen. Hujar and Rosenkrantz hit every part of the apartment, from the dining table to the kitchen to the couch to the rooftop to the bed, shifting the blocking and dynamics each time. Alex Ashe’s cinematography captures the changing of light in a way that adds poetry to the proceedings, while the different scene setups imply an intimate friendship between the interviewer and the subject.

We are reminded that this is indeed a recreation of a lost recording not only through this artifice, but through acknowledgement of the filmmaking itself. The feature opens on black with the sounds of the set, and Wishaw – not sure if he’s Hujar yet – standing in the apartment elevator, while a clapboard comes out to slate the scene. As the film winds on, there are other reminders: jump cuts, wider shots with boom mics or crew members in them, film reels running out mid scene.

None of these devices are particularly revolutionary in 2025, but they serve as a clever reminder of the unreliability of the whole endeavour. Hujar himself may be embellishing – he admits telling a frivolous lie during the previous day, who’s to say he hasn’t added some new ones? And then there’s the source transcript – editorial choices may have been made for clarity or ease of reading, or the transcriber might have misheard something. And if we don’t know the time or where in the apartment the interview took place, why worry about it? The film is ultimately not about any of these details, but about the ability to reframe our understanding of what we do, and articulate it with friends.

Reviewed on: 14 Feb 2025