Eye For Film >> Movies >> Love Me Tender (2025) Film Review

Love Me Tender

Reviewed by: Marko Stojiljkovic

In divorce and custody battles, courts have the thankless task of listening to both sides’ claims, no matter how outrageous they might be, making the procedures unnecessarily long and the “industry” and bureaucracy created around them abundantly “oiled up”. Noah Baumbach used some of his own experiences with the machinery to make his near-masterpiece Marriage Story (2019) to expose how things work even when both parties are “normal” and decent people with their child’s best interest in mind.

The simple and ugly fact is that the side that is first to “pull the trigger” usually has the advantage and can dictate terms, while the other has to comply. Usually, the men are those who leave the family behind, so women sue their ex-spouses for full custody and alimony, while the legal system, at least the Continental one, favours the simplistic traditional image of a father as a breadwinner and a mother as a caregiver. However, there are exceptions to the rule with more factors involved, also explored in divorce dramas, such as Robert Benton’s Kramer vs Kramer (1979).

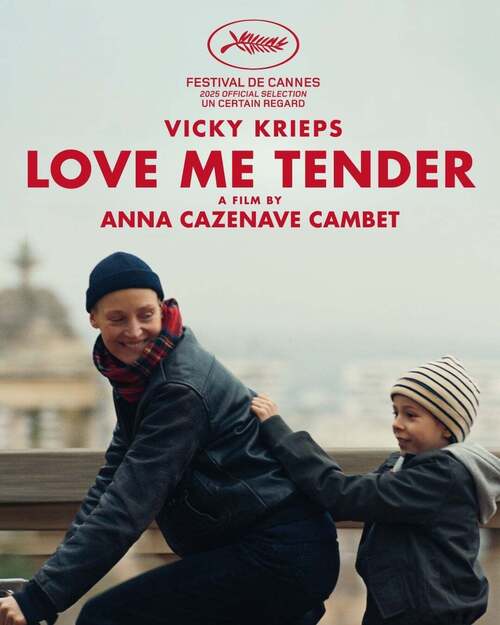

The experience of Clémence (Vicky Krieps), the heroine of Constance Debré’s auto-fictional novel Love Me Tender and Anna Cazenave Cambet’s adaptation of it – which premiered in Un Certain Regard at Cannes – is such exception. She thought she was going through a civil separation with her ex partner Laurent (Antoine Reinartz) after a 20-year relationship from which they have an eight-year-old son Paul (Viggo Ferreira-Redier). The joint custody deal worked just fine, until Clémence admitted to Laurent that she has moved on to dating women. Her coming out motivated him to start an exhausting custody battle laced with accusations, lies and the abuse and instrumentalisation of the kid’s sentiments, wishes and emotions, both the passing and the lasting ones.

As we follow her fight against her ex-partner’s volatile actions, as well as the system’s inertia and rigidity, while also trying to succeed in her new career as a writer, time passes and the mother and son grow further apart. Clémence also struggles to partner up again in a meaningful way, but, until she meets Sarah (Monia Chokri), she also has to experience a string of hook-ups, one-night stands and attempts of relationships with women incapable of or unwilling to help her carry her weight. Luckily, we get to see Krieps in every scene in the film. The star actress from Luxembourg rose to fame gradually until her big breakthrough in Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Phantom Thread where she played the role of a model turning cards on her abusive boyfriend and boss. Krieps has continued picking demanding and challenging roles of women dealing with exceptional emotional pain and, even though those movies were not all memorable, her performance would usually be.

Krieps operates at her usual level of greatness, and Anna Cazenave Cambet does her a favour by putting her in the spotlight, further spiced up with very good camerawork by Kristy Baboul that zeroes in on the actress’ face and the faces of other actors that play characters somewhat sympathetic to Clémence, but unable to help her in any meaningful way. The filmmaker also knows where to place some perfectly executed “peak” scenes, such as Clémence’s casual and passionate hook-up at a swimming pool dressing cabin at the beginning, her first supervised encounter with Paul after two years in the middle of the film, and its darkly poignant ending that defies the viewer’s expectations.

But, as we are so focused on Clémence, we never get to see Laurent’s side of the coin and what motivates him to act like a jerk. The easy answers would be conservativism, machismo and homophobia, while some more insightful answers would combine sheer opportunism with ego wounded by rejection. In the end, it does not matter, as both the author and the filmmaker are not much interested in him and simply see him as a villain. That attitude is legitimate, but it also poses a risk to the movie as a whole.

To be frank, it is about the excessive runtime of 134 minutes, much of which can be described as getting lost in repetitions, idle running and cul-de-sac subplots, such as the one with Clémence and her ailing father (Féodor Atkine). That, along with the explicatory voice-over narration, might come from the fact that the filmmaker adapted the source novel in a too literary fashion, which comes as another proof that things tend to work differently in different media, and the “paper” is more tolerant than the “tape”. Not even the acting powerhouse Vicky Krieps is equipped to save Love Me Tender from the shortcomings sourced elsewhere.

Reviewed on: 24 May 2025