Eye For Film >> Movies >> Edge Of The Night (2025) Film Review

Edge Of The Night

Reviewed by: Edin Custo

The sentence that trails off at the edge of James Joyce’s notoriously circular novel, Finnegans Wake, would make a fitting epigraph for Vladimir Loginov’s Edge Of The Night, another work that begins nowhere in particular and keeps circling back on itself. Built from nocturnal fragments of Tallinn shuffled out of chronological order, Loginov lets the city drift in and out of focus until dusk and dawn blur, and night stops feeling like a time of day and becomes a state of mind.

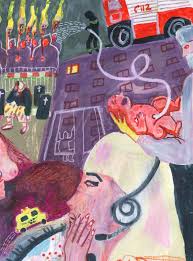

The guiding structure is simple: a series of vignettes that alternate between those who work through the night and those who live in it. On one side are the people who keep the city running while everyone else sleeps, including an emergency services call centre operator, hospital workers, a bus driver, firefighters and an air-traffic controller, most of them tethered to screens. Monitors, dashboards and phone displays glow in the dark; the frame is constantly punctured by small, artificial rectangles of light.

On the other side are Tallinn’s night-dwellers: bodies colliding in clubs and sex dungeons, drunk karaoke in a cozy bar, beachside hangouts that end in cold-water plunges and sauna steam, kids high and giggling as they tag walls, a far-right rally. These scenes are less about sociology than texture: the way club lights pulse, fog hangs and sound bleeds from one space into another.

Binding these fragments together is a whispery, poetic narration by an insomniac voice (Tom-Olaf Urb), seemingly wandering the same streets we see. His reflections, such as “at night, despite the darkness, there are countless bright, colorful spots” and “night, like salt, enhances the taste of darkness”, could easily have tipped into cliché, but the delivery is hushed and intimate enough to feel like thoughts you might have half-awake, staring at the ceiling. The sound design folds his murmur into a dense soundscape of sirens, engines, club bass and distant chatter, so that the film works as much on the level of listening as looking. This is a documentary that really should be watched at night; daytime feels like the wrong operating system for it.

The Finnegans Wake connection emerges most clearly in the circularity. Much like Joyce’s book, which famously loops its ending back into its opening, Edge Of The Night gestures towards a cyclical, never-complete vision of experience. The closing sequence in a recycling plant makes that metaphor literal: mountains of waste are sorted, crushed and processed under harsh industrial light. It is an oddly beautiful, almost abstract finale, hinting that the city’s nights are also part of a broader cycle of use and discard, of bodies, objects and experiences constantly being transformed and fed back into the system.

For all the bustle, what lingers is how alone many of these people are. Loginov repeatedly isolates figures in low-lit rooms and cabins: the call operator at her desk, the driver in his car, the worker watching a conveyor belt crawl past. Even revelry is often framed from a slight distance, as if the camera is leaning in from the outside. While never underlined, you can feel a quiet comment on contemporary loneliness running beneath the surface: a city full of people awake at the same time, yet separated into sealed pockets of light.

There is also a linguistic layering that hints at Estonia’s geopolitical and cultural tensions. Estonian and Russian can both be heard throughout, though the director wisely resists turning this into a didactic essay on national identity or Estonia-Russia relations. Instead, the coexistence of languages becomes one more texture of the night, another reminder that cities are made of overlapping realities you can’t fully grasp from a single vantage point.

If Edge Of The Night has a limitation, it is inherent to its concept: by design, it trades depth for breadth. No single subject anchors it, and some viewers may miss a clearer narrative spine. But that feels like part of the point. Just as no single reader can fully “master” Finnegans Wake, unless you are one of those die-hards in Venice, California who spent 28 years going through its not-quite 700 pages, no single person can experience all the edges of a city’s night. Loginov does not pretend to. He just keeps circling, drifting, listening, letting the night fold and refold until it yields a kind of exhausted, luminous clarity.

Reviewed on: 14 Nov 2025