Eye For Film >> Movies >> Camille Claudel, 1915 (2013) Film Review

Camille Claudel, 1915

Reviewed by: Jeff Robson

What happens to the muse of a great artist when she ceases to become his inspiration – and has a talent that demands recognition in its own right?

The answer’s a pretty bleak one in Dumont’s stark but rewarding biopic, which focuses on the later years of Camille Claudel, who met Rodin when she was a student in the Paris of the 1880s and already beginning to win a reputation as a sculptor. She became his collaborator, model, inspiration and lover, though the relationship soured when he refused to leave his lifelong companion (and eventual wife), Rose Beuret.

It’s a cracking true-life story, and Bruno Nuytten’s 1988 retelling, starring Isabelle Adjani and Gerard Depardieu, was a tempestuous fin-de-siecle love story. Dumont’s take is a different piece of work altogether – an inward, austere examination of ideas of madness, empathy and the creative impulse.

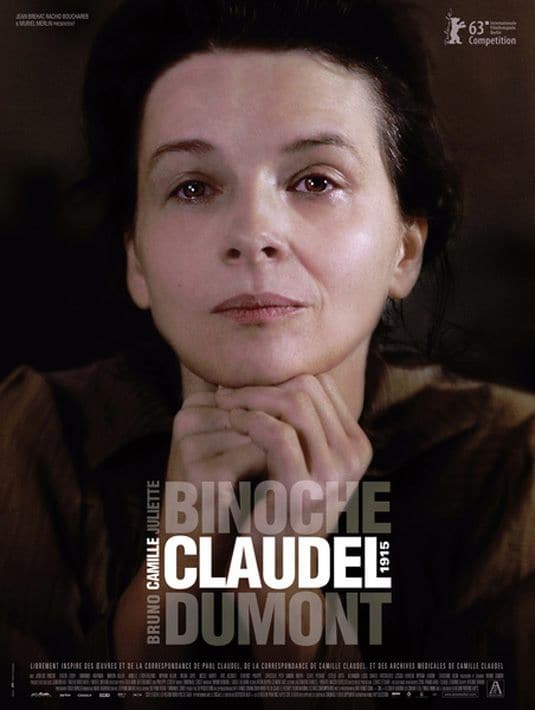

Set in the year of the title, it’s more than two decades since the relationship with Rodin ended. Camille (Juliette Binoche) is now a middle-aged woman and her family, increasingly worried by her mental state, have confined her to an asylum near Avignon run by a religious order. Lucid but paranoid, she finds it increasingly hard to bear the company of her fellow inmates, most of whom are severely mentally handicapped and unable to engage in even the most basic human interaction.

She regards Rodin as the author of a conspiracy to deprive her of her studio and her livelihood, pinning all her hopes on a written plea for help to her younger brother Paul (Jean-Luc Vincent), a Catholic visionary poet and novelist. As she waits for his arrival, Dumont focuses with a Bressonian documentary intensity on her day-to day routine.

Most of the supporting cast are played by real-life mental patients and Camille’s sense of displacement and torment is harrowingly realised as she is alternately repelled by their constant, unsettling presence and touched by occasional acts of elemental kindness that transcend our definitions of ‘sanity’. The black-cowled nuns who shadow her movements, looking like Bergman’s Death and offering pious platitudes rather than professional medical care, are an additional burden and even the asylum’s director (Robert Leroy) is regarded less as an intellectual equal and more a sounding board for her diatribes against imagined persecutors, which morph into poignant recollections of her old Parisian life.

Meanwhile Paul has received her letter and is travelling to the asylum. But as he breaks his journey at a nearby monastery and indulges in a lengthy dialogue about his own creative and spiritual history with a priest (Emmanuel Kaufmann) it becomes clear that he regards his sister’s illness as part of God’s inexplicable, unchallengable design. And that when the two meet, their conversation will decide Camille’s future...

This isn’t an easy, entertaining watch by anybody’s standards. But those familiar with Dumont’s work will find that no surprise. In all seven of his films, and especially his two most recent, Hadewijch and Hors Satan, he’s focused with often controversial intensity on physical, mental and spiritual extremes with few concessions to mainstream sensibilities. But he has a novelist’s ear for the telling phrase and the compelling exchange of dialogue, coupled with a painter’s eye for a striking image. The tranquil beauty of the Provence countryside contrasts vividly with the monolithic austerity of the church buildings that dominate Camille’s (and to some extent Paul’s). And the Spartan interiors convey the grim reality of the inmates’ limited, monotonous world.

He’s conjured up a selection of first-rate performances too. Binoche is a study in restrained intensity, eschewing the usual irritating tics of actors doing their awards-pitched ‘mad’ turn to create a simple, poignant portrait of a woman who’s seen all the certainties of her life overturned. She’s matched by French theatre veteran Vincent, who brings a scarily unbending intensity to his role as the buttoned-up, self-righteous Paul, seeming to relish the power he holds over his wayward sister’s fate. Leroy and Kaufmann as their respective confidantes contribute subtle, unshowy turns.

The ‘performances’ of the real-life mental patients are remarkable too, though perhaps laying the director open to charges of exploitation. I’m sure all the necessary permissions were obtained and appropriate guidelines followed but I was left with the sense of a rather too literal quest for ‘cinema verite’ (and perhaps a bit of deliberate controversy-courting). It’s a decision that’s in keeping with the film as a whole, however, which asks us to examine our ideas of how insanity is defined and treated, as well as the perception that those blessed with the gift of creativity suffer more than most when it strikes. Camille Claudel 1915 is a far cry from the usual ‘genius as madness’ artist biopic, and all the richer for it.

Reviewed on: 15 Oct 2013